Blog post with formatting tips for you

"I'll tell you somebody who…. contributed to the vibrancy of the Dublin that mattered and that was Yvonne Jammet…"[1]

In Dublin, the name 'Jammet' is associated more with fine dining rather than the fine arts. The story of the journey of Michel Jammet to Ireland in 1887 and with him the arrival of 'haute cuisine' to Dublin 4 has been published in 'Jammet's of Dublin', describing the family and their business success story; a team of 'highly skilled chefs and waiters, haute cuisine food and presentation, experienced and dedicated management – all these combined to create the exceptional confection that was Jammet's'[2]

But this story began in France with Yvonne Auger, an artist, who studied at the Académie Julian in Paris. After her marriage to Louis Jammet in 1922, the couple settled in Northern France and had two children. Louis' father, a restaurateur in Dublin[3], was looking to retire and return to France, so his proposal to Louis and Yvonne to take over the running of the restaurant meant a move to Dublin. While Louis had spent his youth in Dublin, Yvonne was born in Paris and this was a leap into the unknown, however she was 'excited about making a fresh start in Dublin'[4]. Arriving in Ireland in 1928, they took over a thriving and respected business from Louis' father Michel, who returned to France.

Life in Dublin

In his memories of the Dublin art scene, art dealer Victor Waddington remembers Yvonne Jammet's 'fantastic moral courage', her support and encouragement for artists. Along with her husband, restaurateur Louis Jammet, whose 'material support' was a welcome intervention for artists - the pair became well-known in Dublin. Their life was not confined to Nassau Street or culinary experiences as both 'immersed themselves in Irish culture…. sponsorship of the arts….'[1] With Yvonne travelling outside the Dublin environs, opening an exhibition in Limerick[2] and creating sculptures for a parish church in Limerick[3] and exhibiting in the Tuam Art Club's exhibition in Co. Galway[4].

Living

in 'Kill Abbey' near Monkstown, the Jammet house, with its own grounds, was

large enough to accommodate a studio where Yvonne continued her art practice.

Although known for her paintings of French village and country scenes, she was

also skilled in needlework creating tapestries and banners and exhibited her

work in this medium, …a large three-yard square tapestry of the Battle of

Clontarf…with much study of military and costume history'[5].

[1] Victor Waddington quoted in Harriet Cooke talked to Victor Waddington, the veteran art dealer, about his memories of Dublin, The Irish Times, Wednesday 26 June, 1974

[2] Maxwell, Harpur. pg.17

[3] Jammet Hotel and Restaurant opened in 1901

[4] Maxwell, Harpur, pg.35

[5] Ibid, pg.65

[6] Goodwin Galleries, Limerick. (Sunday Independent, 26 October 1947)

[7] Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Limerick

[8] '50 pictures by Irish Artists for Tuam exhibition', Tuam Herald, Saturday, 31 March 1945

[9] Irish Independent, 18 March, 1960

These skills evidenced in her costume designs for the Gate Theatre in Dublin '(she has) a keen interest in the designing of stage décor and costumes. The costumes for the Dublin production of Pygmalion being done by her'[1].

The Jammets were patrons of the Gate Theatre and both the theatre founders Michael MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards dined at Jammet's and were considered friends, joining Yvonne and Louis as well as their four children for many Sunday lunches.[2]

Described as 'an elegant woman', Yvonne also made her own hats and through the restaurant, was exposed to the work of Irish designer, Sybil Connolly as well as keeping an eye on Paris fashions. Both Jammets were members of the French benevolent society, Louis serving as vice chairman and Yvonne as honorary secretary. Yvonne was also a member of the United Arts Society, exhibiting in their member exhibitions; "very effective studies of the French urban scene"[3]. The role that Yvonne placed in the Irish art scene was certainly considered relevant enough to list her among the 'distinguished and successful exponents of contemporary tendencies in art' alongside Mary Swanzy, Evie Hone and Mainie Jellett.[4]

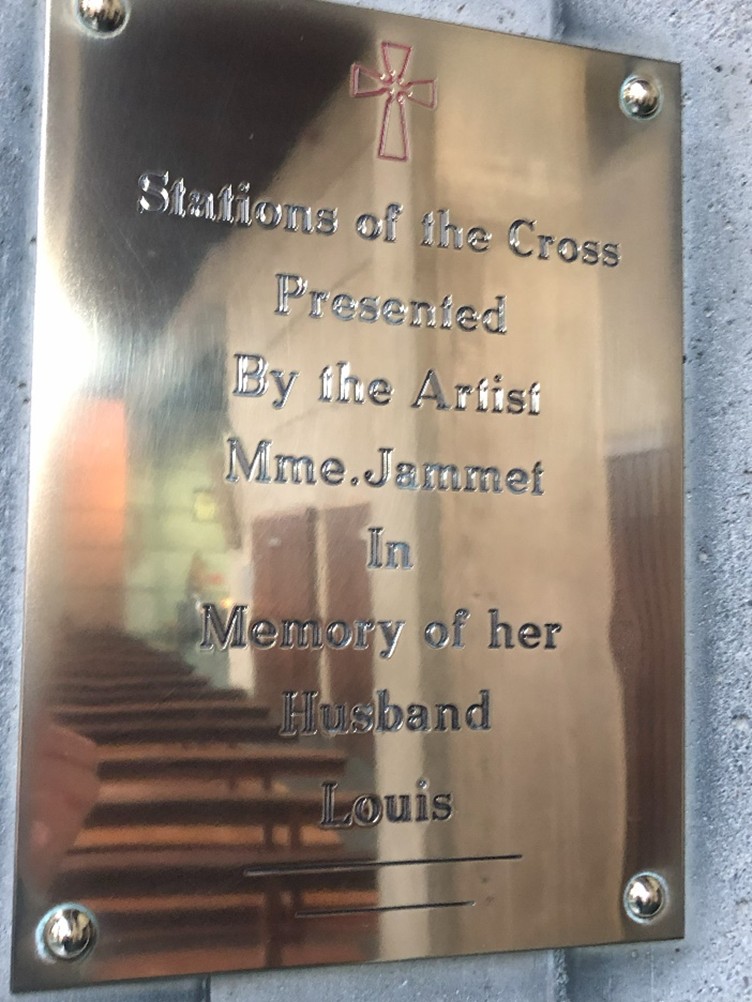

Tribute to Louis Jammet

"She wants to do a stations of the cross in wood"[5]

The placement of art in churches, their purpose and design, was a way of bringing religious text to life, using the power of the visual to inspire and reflect. In St. Michael church, Dun Laoghaire, as in many churches, various art forms are used for this purpose, and many are embraced; stained glass, sculpture, metal work in doors, windows and niches. St. Michael's has an austere exterior where unfortunately the viewer cannot glimpse from its exterior the many artistic wonders inside.

The interior height of the church also means that any artwork will be competing with not just the scale of the space but also, due to most of the few windows being stained glass, the unpredictable nature of the availability of light.

Depicting the Stations of the Cross is a considerable undertaking for any artist, no matter the medium, a challenge for a fresh take on a story that is 'commonly found on the walls of all churches of the Latin rite....'[6]

The

year of the completion of these stations is not clear. Jammet seems to have

exhibited a cycle of Stations of Cross in Dublin in 1946[7]

and also in 1956 with the former mentioning the medium

of 'wood carving' while the review of the latter exhibition was more specific

referencing 'a lovely set of Stations of the Cross carved in mahogany[1]'.

[10] Irish Press, 13 February, 1941

[11] Maxwell, Harpur. Pg.56

[12] Irish Independent, Art critic, 15 February, 1952

[13] Kennedy, S.B 'Irish Art & Modernism', p119

[14] Irish Independent, Art critic, 15 September, 1951

[15] p6. The Way of the Cross – a Journey with Images and Words of Scripture Carved in Stone, Ken Thompson

[16] Exhibition by Yvonne Jammet, Irish Press, Wednesday, 10 April, 1946

[17] 'Challenging work at sculptures exhibition', Irish Independent, Tuesday, 8 May, 1956

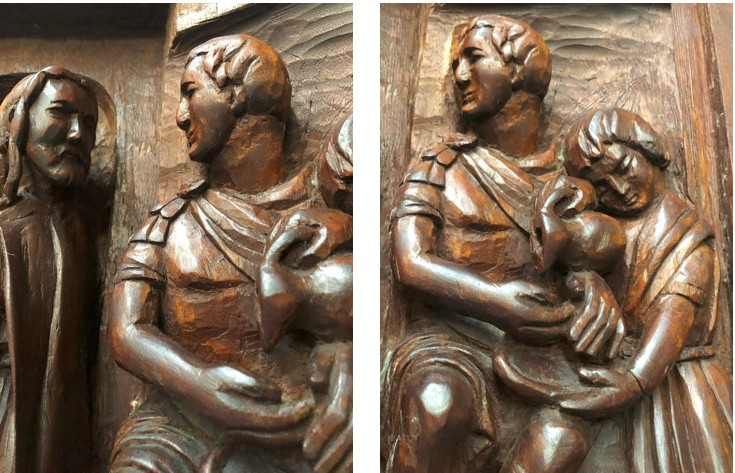

Taking over three years to finish the fourteen separate episodes, Jammet's stations are created from dark mahogany wood, and they hang against a polished concrete wall. Each measuring roughly 58.5cm x 61cm and just under 10cm deep, they are placed along the back wall of the church, facing the altar, the fourteen Stations are separated by two long vertical inserts of stained glass; in an abstract design[1], (see fig. 6).

Jammet's Stations are not visibly numbered. The viewer moves along the wall and views, slightly above eye-level, the stations from right to left.

This is a story well told from medieval times, found mainly in religious settings, churches, cathedrals. But it is not simply told and here Jammet has opted for multiple figures, no numbers and no descriptions. This is a cast of many and while Christ is the central figure, you could easily lose sight of him among the melee of figures, in this ancient time and place; Jerusalem.

[1] Stained glass work by Johnny Murphy and Terry Corcoran,1973

Fig. 1 Interior with sixth station in the foreground, Veronica wipes the face of Jesus. St. Michael's Church, Dun Laoghaire

Holding the chaos

The first station 'The Condemnation of Christ' is constructed by the artist with the action of Pilate washing his hands; saying so much without words - a sign of cleansing, aware of the deed of handing Christ over to the people for crucifixion.

However, Jammet has set the two protagonists; Christ and Pilate eyeballing each other (Fig.2) and we see Pilate, oblivious to the young boy who holds the plate of water - the ultimate 'washing his hands 'of the toxic situation.

This intensity had been played out earlier, at the garden of Gethsemane when Judas betrayed Jesus. As the only interior scene, Jammet has set a recessed door behind Christ, while Pilate is seated on his throne underneath a canopy (Fig.3).

The rope tied around Christ's hands (Fig.4) are on par with the bowl Pilate washes his hands in – the former a direct consequence of the latter. The figures on the left work on their task, behind Christ, so as not to fill the ground between the two main figures. In a way this is the strongest depiction in Jammet's Stations, a direct link, a powerful interaction that begins the unfolding of the story. Jammet has placed Pilate on a false throne, although slightly more elevated than Christ who is standing. At this point we get a foretelling of the tipping of power of the Roman empire.

Fig. 2 (left) Detail from first station, Jesus is condemned to death. Pilate and Jesus review each other

Fig. 3 (right) Detail from first station, Pilate washes his hands

Photo gallery

Above images: Fig. 4 (first column) Detail from first station, Jesus is condemned to death. Jesus' hands are tied.

Fig. 5 (second column, top) Second station, Jesus takes up his Cross

Fig. 6 (third column, top) Detail from seventh station, Jesus falls for the second time

Fig. 7 (fourth column, top) Ninth station, Jesus falls the third time.

Fig. 8 (third column, bottom) Detail from eleventh station, Jesus is nailed to the Cross

Fig. 9 (fourth column, bottom) Twelfth station, Jesus dies on the Cross

Fig. 10 (second column, bottom) Hidden gem - interior view from altar to back of church towards a selection of stations by Yvonne Jammet, St. Michael's Church, Dun Laoghaire

Although all of the stations are packed with figures and set within confined squares, in this station, Jammet leaves a space between Pilate and Christ that extends nearly to the base of the scene which further emphasises the gaze and the chasm between them.

All the servants look elsewhere, which further accentuates the link between Pilate and Christ – the only figures looking at each other.

Just how heavy was the cross for one man? We get a sense of this in the second station in the posture of the man on the left. The cross on his shoulder as he grips his right knee to balance himself, a very honest reaction, and shift the weight to Christ, leaning on him for support (Fig. 5). We see the impossibility of this scene within the tight space, trying to settle the burden of the Cross on one man.

Jammet includes bystanders in this station, figures moving in the dark, observing. Her stations are a 'window' on the chaos taking place on the streets of Jerusalem as people pushed, rushed and gathered trying to get near the action. And as viewers, Jammet has given us a small opening into that chaos.

In her art practice, Jammet transitioned between paint and canvas, needle and yarn to chisel and wood, some works not requiring too much emotional substance – villages, landscapes. But to tell 'the greatest story ever told', with the focus on one man, the work must be emotive and bring the viewer along that journey and should cause them to reflect – or it is not a success. There is no other reason to depict this story of brutality, it is already well told – the challenge is the emotional content and the skill in conveying this to ignite the viewer into reflection.

At the fourth exhibition of the Institute of the Sculptors of Ireland at the Municipal Gallery, a critic noted that Jammet's "stations of the cross, all 14 of them in mahogany, are very sincere in conception……if one reads their meaning in terms of the emotional idea, they are admirable"[1]

Placed at eye level, not high up the church walls or at the end of pews where one is constricted in stepping back for a wider view, Jammet's stations are at odds with the modernity around them. Not only the modernism of the church architecture, but also the abstract glass windows by Patrick Pye, altar furniture by Michael Biggs and the tabernacle by Richard Enda King. As Pilate before us, we eyeball the scenes, get up close and witness – Jammet has created uncomfortable viewing.

And now through the stations that follow, it is the emotion that will bring home the suffering – the distress of the women in the third station juxtaposed with the bored look of the soldier on the right.

In the fourth station, the anguish on the face of his mother, arms wrapped in self-comfort, in comparison to the acceptance on the face of Christ. Jammet has placed the Cross further back in this scene to allow the focus on the human emotions as she concentrates on the key element - the human story; a mother and her son. Interestingly, both figures are looking out, not at each other - although there is a touch, a hand of reassurance.

Despite the help of Simon of Cyrene, Jesus falls a second time and this is a more brutal depiction – the solider raising his arm to strike Christ with his baton. The dramatic reach of the woman/man on the left forms a pyramid of narrative where the other figures in the station are almost redundant. All is chaos; love and hate.

[1] 'Brave exhibition of sculptors' work', Irish Press, 8 May, 1956

An enquiry

After the third fall, there is scepticism that Christ will be able to complete the journey. He is on the ground being pulled by a soldier on the left, while on his right a conversation is taking place – is he able? Is he strong enough to go on? The pain in Christs' face, in this ninth station (Fig.7), is in contrast to the kneeling soldier, insistent on the journey taking place. The interlocking of limbs and forms here are a credit to Jammet who conveys the chaos of the time, utilising not just extra figures but, with their postures and actions, they are a 'snapshot' of a moment on the road to Golgotha.

Has he just hit his thumb?

On arrival at Golgotha, several men get to work observed by the soldier on the left in the eleventh station. The procession has finally arrived at the rock and here we see men tasked with nailing Christ to the cross - bent down, intent on their work (Fig.8). It is hard to identify through the chaos of figures each individual - their place in the story, but Jammet sees them all as witnesses, partaking and observing - creating separate actions and positions for this group. We see one of the men sucking his thumb, a very human response to a common accident.

If proof be needed

The twelfth station; the cross divides the narrative – a division of emotions and responses to Christ and his life of teaching.

Christ welcomes all. In his reach across this part of the narrative (Fig.9) with hands stretching across the confined space; on the left his mother and friends, on the right, the populace. The soldiers' sword raised to pierce Christs' side to witness blood and water, and opposite; a portrait of a mother in grief.

After the passing of her husband Louis in 1964, Yvonne Jammet moved out of Kill Abbey to Ailesbury Road. The following year, not far from her former home, fire took hold at St. Michael's Church in Dun Laoghaire, necessitating a rebuild. Jammet's exceptional gift to the new building must have been offered within the two years prior to her death in 1967, but in the end, she was unable to see her Stations hung at the new St. Michael's Church in 1973.

Jammet (Dublin) – August 30, 1967. Yvonne, widow of Louis J, 61 Ailesbury Road, deeply regretted by her children, relatives and friends. R.I.P. Remains will arrive Church of the Sacred Heart, Donnybrook at 5.15 mass to Dean's Grange Cemetery [20].

[20] Irish Independent, Friday, 1 September, 1967

The author would like to thank Alison Maxwell for her advice on this article. Alison re-established contact with Yvonne Jammet's nephew, however due to ill-health in the family he was unable to be interviewed for this essay. Further work on Jammet's art and life in Dublin is currently being undertaken by the author.